Features

Environment & Sustainability

Forestry

Pulp

Aerial advantage: UAVs and big data are changing the fibre supply game

August 2, 2019 By Maria Church

August 2, 2019 – With forest companies industry-wide facing fibre accessibility challenges, the name of the game today is supply chain optimization.

A technology company based in Vancouver believes the solution is in forestry-specific data collection and analytics.

Big data – a buzzword for the storage and analysis of large, complex data sets from multiple sources – has taken most industries by storm. Technologies such as drones, LIDAR, radio-frequency identification and various equipment sensors allow companies to collect seemingly endless amounts of data, but it’s the practical application that is somewhat elusive to the forest sector.

Mike Wilcox, co-founder of FYBR Solutions along with Patrick Crawford, says the end goal of all data and analysis in the forest sector is to better understand and optimize supply and production. “We specialize in the use of drones, but they are just the tip of the iceberg,” Wilcox says.

“Our goal is to get as much information as far up the supply chain as possible because it has a cascading effect on downstream operations,” he says. “We are supplementing traditional data sources with this individual stem inventory, which gives the people on the ground the ability to make more informed decisions.”

Drone beginnings

FYBR began in 2014 as Spire Aerobotics Inc. – a drone company for the natural resources sector. The company has since rebranded as FYBR Solutions to reflect what the team had quickly learned: In order for their drones to solve real-world problems, they needed to provide a turnkey solution for just one industry.

“Forestry really hit home for us, not only in terms of where we are geographically – Vancouver is where a lot of the big forestry companies have their headquarters – but we both grew up in small towns where forestry is the number one driver. It’s rooted in who we are,” Wilcox says.

Conversations with industry gave the company purpose. The goal became to understand challenges in the forest sector and to cater different technologies to solve problems. Drones (also known as UAVs – unmanned aerial vehicles) are still a large part of what the company offers, but they also work with satellite data, ground data and more. The more information they collect and analyze from all points of the supply chain, the better they can offer optimized solutions to mills.

Wilcox says the company blurs the lines between a service, a software tool and a hardware solution. At some mills, they have deployed drone systems and provided training for the mill employees to collect data on their own. FYBR then receives and analyzes the data to provide measurements at various stages of the supply chain, such as the measurement of log decks or chip piles, or the accuracy of mature stand surveys for harvest planning.

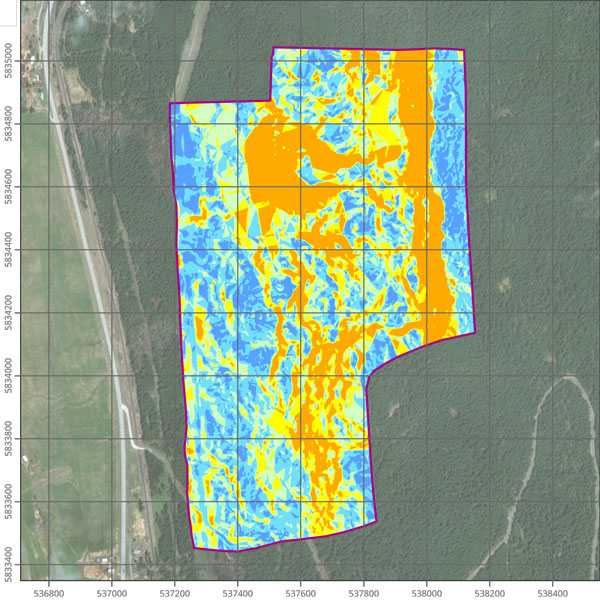

FYBR’s drones are used to collect a range of data on forest volumes, health and boundaries.

Pulp inventory

West Fraser Hinton Pulp in Alberta is a FYBR client. The pulp mill west of Edmonton is continually measuring its chip pile to understand usage and inventory balance.

Garry Power (now retired) was the divisional controller for the pulp mill, and worked closely with FYBR to create 3D models of the chip pile to determine volume. Power then compared the volume found by the drones, factoring in compaction, species, etc., with physical measurements taken on the ground. “The more information and the more numbers you have to work with, the better,” says Power. “Then we can start looking at where we are losing fibre through our system.”

Aside from measuring volumes, Power says the drone can help mill staff perform inspections of the pulp tanks. “Normally we have to take outages, drain the tanks completely, scaffold them up and do a physical inspection of the tank to determine repair plans. We’re looking at flying a drone inside the vessel to take pictures and thermal measurements instead of inspections. Even avoiding scaffolding would be a huge savings,” Power says.

Hinton Pulp contracts FYBR on an as-needed basis, but Power expects the applications for drones will continue to grow as the technology to analyze the data develops.

Drones such as FYBR’s (pictured) must be equipped with appropriate sensors and paired with the correct data management system in order to be effective.

Silviculture surveying

Another of FYBR’s clients is Interfor’s Kootenay Division in the B.C. Interior. Silviculture forester David Jackson is working with Wilcox and Crawford to develop a reliable method of silviculture survey using drones that is legally acceptable to the forest service. Interfor collects the drone data and FYBR analyzes the information to develop inventory maps for brushing treatments. “Silviculture surveys are [traditionally] done with boots on the ground, so a drone can certainly speed up that process. Hopefully in the future it will reduce survey costs and increase the precision as well,” Jackson says.

Jackson operates on two tree farms and a forest licence, working out of Nakusp, B.C., for Interfor’s Castlegar mill, where they cut approximately 2,000 hectares a year.

This year, the mill leased a drone from FYBR to fly cut blocks, checking for post-harvest obligation commitments such as the logging boundary, road building, blocked ditches or culverts, and assessing waste volumes. Jackson and a few other staff received training from FYBR to operate the drone, but it’s steep learning curve, he says. His first flight ended with a drone in the tree. “It’s been a hard thing to live down!” Jackson says.

Time is the biggest obstacle for the Interfor staff, Jackson says. “We’re probably not using [the drone] as often as we’d like to,” he says. “We have good intentions to use it also for log inventory at the sawmill as well, but that hasn’t happened yet. It’s still in a testing phase.” Weather is also a limitation since drones are not operable in heavy wind and rain.

The cost considerations are difficult to determine, since it’s a product with data never before used. The question is, what will they get out of all that data? Jackson says Interfor hopes to cut down on the cost of hiring consultants for post-harvest commitments. And they will continuing working with FYBR to find other ways of optimizing their fibre supply processes, whether it’s in the layout of cut blocks or assisting their logging contractors on, for example, skidding distances and cycle times.

Technology curve

Part of the challenge in working with drones and other emerging technologies is that they are developing at a rapid pace. The applications for drones in forestry are continuously being improved upon, Wilcox says, making reports from as early as a year ago outdated. That also means the possibilities for the technology are limited only by current imaginations.

In precision agriculture, drones with multispectral sensors are being used to survey crops and determine areas where the crop is unhealthy from drought, overwatering or pests. The same concept can be applied for forestry, Wilcox says. Drones can be used to identify tree species and health indicators – information that could be invaluable to forest management and planning.

FYBR works with master’s students from the University of British Columbia’s Integrated Remote Sensing Studio to analyze the data they’re collecting in the field. “UBC has been a great research partner to answer some of these questions in a more academic, rigorous setting to make sure our results are reliable,” says Wilcox.

Each of these emerging technologies – lidar, radio-frequency identification, drones, mobile transportation tracking, and so on – can offer value to the forest industry, but FYBR’s end goal is to create a single integrated system that digests all the data and provides insights into fibre flow. These insights will help a company save time and money, and plan for the future.

“It starts with that siloed approach, proving those pockets of value, but the big picture is tying those values together,” Wilcox explains. “We are connecting the sawmill with the forest operations, with the sales people and with the accountants. That information transparency is what will have the greatest impact on efficiency and sustainability in the long run.”

That means FYBR is technology agnostic, Wilcox says. “We to use whatever tools are available to fill the information gaps in order to achieve a complete view of the fibre supply chain. Then we can identify opportunities for optimization.”

FYBR Solutions has drone systems deployed at sawmills and pulp mills in Western Canada, and in the hands of foresters collecting data. The company is also in the midst of branching out to Eastern Canada and the U.S. As FYBR collects more data, it’s fine-tuning its system and planning new ways to offer more value to forestry clients.

Mike Wilcox, right, and Patrick Crawford are the co-founders of FYBR Solutions, a technology company based in Vancouver looking to solve fibre supply challenges with forestry-specific data collection and analysis.

Drones 101

FYBR Solutions co-founder Mike Wilcox says there are two main challenges to working with drones in forestry.

The first challenge is the reality that a drone pilot is an airspace user, which means he or she must abide by regulations from Transport Canada. The rules are a necessary way to ensure the safety of everyone involved, Wilcox says.

“If you are putting a two-pound piece of equipment up 300 feet above the ground where helicopters or planes are operating, you want to make sure it’s safe and you’re not putting anyone at risk. Especially when these systems have the potential to be used negligently or irresponsibly,” he says.

Current Transport Canada regulations require that all drones, for commercial or private use:

- Fly no closer than nine kilometres to forest fires, airports, heliports, aerodromes, or built-up areas

- Do not fly over military bases, prisons or in controlled or restricted air space

- Do not fly over crowds higher than 90 metres

- Do not carry dangerous goods or lasers

- Fly only in the daylight, within line of vision

- Commercial drones more than 25 kilograms must apply for a special flight operations certification. Those under 25 kilograms can apply for exemptions, but must adhere to dozens of conditions. New, more straightforward rules are expected in the coming months from Transport Canada.

The second challenge in working with drones, Wilcox says, is managing expectations. “A lot of people think you can just buy a drone, sit in your office, send it out the window and work the joystick. Then you fly it back and you have the information that you’re looking for. That’s just not the case,” he says.

Even if a drone is programed to autonomously fly a particular route, drone users are still required to monitor the air space and be ready to take over piloting if a problem arises.

From a data standpoint, the drone must be equipped with the right sensors and paired with the right data management system for it to be effective. “Without those you’re just getting a camera up in the air to take some pictures and get a look at things,” Wilcox says.

Drone applications for forestry include inventory audits and tracking, harvest planning, post-harvest obligation survey, post-wildfire salvage, equipment inspections and silviculture surveys.

_____

Maria Church is the editor of Canadian Forest Industries & Wood Business. This article originally appeared in Wood Business.

Print this page