News

Maximizing Potential

March 1, 2008 By Pulp & Paper Canada

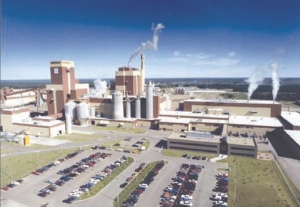

Canada's newest and largest kraft pulp mill

Canada's newest and largest kraft pulp mill In a perfect world every Canadian pulp and paper mill would operate in continual ‘Goldilocks’ mode; every component, system and person hums along at the optimum. Not too hot, not too cold but just rig…

In a perfect world every Canadian pulp and paper mill would operate in continual ‘Goldilocks’ mode; every component, system and person hums along at the optimum. Not too hot, not too cold but just right.

The control operators could relax, the accountants upstairs might allow themselves a small, fractionally precise smiles, the tasks of men and women checking gauges and scribbling on clipboards could even become redundant.

But the global pulp and paper arena is full of giants and Canada’s mills are no longer part of this group. Even our newest and largest kraft pulp mill, Alberta-Pacific, is 15 years old, whereas the massive plantation-fed Veracel Celulose in Brazil roared into life in mid-2005.

Brazil isn’t the only big kid on the cut block. Uruguay, Chile, Indonesia, Brazil, Russia and Finland are also pushing into new markets. For Canadian mills facing these odds, opting for sheer expansion is difficult and costly.

To compete, Canadian mills must ‘make do’ and do more with what they have. Coordination, co-operation and alignment of management, workers and government is critical. Rather than fixate on sheer output, reduce the cost-per-tonne. Rather than trying to out-produce huge plantations, cut production costs and compete on price and quality.

Steve Babensee is vice-president/control system solutions and asset optimization for Burnaby-based NORPAC Controls Ltd. As part of the ‘NORPAC Solutions’ optimization team, he believes the industry isn’t so much interested in expanding output but instead is anxious to reduce the cost per tonne of pulp. “And there are tonnes of other issues.”

In front-line mills, this means optimization and superior process controls. Ask optimization experts what’s top of mind with clients and the answers are: energy usage, reliability and wireless technology. That, and help create a proactive ‘can-do’ attitude in the field, upstairs and on the floor.

According to Emerson, there are “significant asset optimization improvements” laying latent in many facilities that are upgrading. Typically, this can mean one to three percent gain in mill operating margins and up to a 50 percent reduction in maintenance costs. In New Brunswick, for example, Fraser Paper realized $2.2 million in annual savings courtesy an Emerson-tailored upgrade of its bleach plant and washing/ screening process.

Like most aspects of the industry, the bedevilments are in the details . . . but so are the solutions.

BTUs, Watts and You

Energy costs are growing, especially for fossil fuels. This won’t change, so learn to use less.

“The amount of energy floating around in a pulp and paper facility is so huge, small percentage changes mean really large economics,” notes Ed Schodowski, global pulp and paper sales director for New York-based optimization experts Emerson Process Management. “When fossil fuels were cheaper, it wasn’t a big deal but now it’s a huge cost that’s kind of snuck up on the industry.”

Schodowski says even “small investments” to cut oil consumption in high-energy ‘consumers’ (e. g. lime kilns and power boilers) can mean savings of US$1 million to US$5 million per annum. The payback time: as short as three months.

Conversely, inefficient infrastructure can spark plant-wide shutdowns. At best, unaddressed energy leakages steadily erode already thin profit margins.

In his article Power Analytics and Business Continuity, EDSA Micro Corporation VP of Communications James Neumann says electrical power outages, spikes and upsurges cost the United States economy US$150 billion plus a year. (Extrapolated, Canada looses about $15 billion a year.)

Most of the loss isn’t due to natural disasters or outside forces (i. e. the public utility on the fritz). It’s from within.

Worries Neumann: “Eighty percent of power problems occur within an organization’s own electrical power infrastructure -not because of external causes.”

Optimization looks within. First off, says Babensee, it tames big energy eaters and smoothes the ‘variability’ of energy usage, making it predictable and flat-line as possible through operator training and advanced process controls.

For example, lime kilns. The fix ranges from the complex -installing many sensors, “pretty fancy software” and precisely tailored control techniques -to the relatively simple: adjusting or ‘flame shaping’ the kiln’s combustion flame. When a kiln is properly “tuned up” to runs at its optimum and yet at the lowest possible temperature. Babensee says the savings can be “up to one million plus dollars a year.”

Efficient mills run power boilers almost entirely on bark and wood waste. “Not-so-good ones use lots of fossil fuels to make the operation easy,” says Babensee. Like many frontline workers, boiler operators are under a lot of pressure not to screw up. The dollars burnt are collateral damage.

“Some mills just love to keep the fossil fuel ‘on’ so it runs more stably. They’re going to run things as comfortably as they can because they don’t want to get ‘run over’ by an unexpected event.”

The solution? Physically adjust the ratios; up the energy from bark, cut the easy fix of fossil fuel and bring it to industry average or industry best. Psychologically, change the operators’ attitudes. Says Babensee: “We’re teaching them to be more comfortable pushing the limits a little more.” The savings can be millions of dollars a year.

A standard optimization implementation strategy can take three to six months. Training and changing attitudes can take forever. “There’s the technology itself and then you have the people who must understand the software and how to apply it,” muses Babensee. “As important as anything is [knowing] how to get people to use it and be comfortable. Sometimes that’s not an easy chore.”

Wireless: Unseen Gets Visibility

Pulp and paper mills are enormous, intertwined organisms. Large and small, critical to secondary, the more and better the information coming in from those components -vibration, heat, pressure, temperature -the better operations can fine tune and control the variables.

Until the advent of wireless sensors, bringing this information home to the control room was costly and difficult. Only the most critical components were tracked; running cables and wires to monitor the myriad of gauges, valves and other components was costly and created crazed spider webs of wires.

Relying on troops of clipboard carriers to monitor the gauges avoids the tangles but is costly in terms of manpower. It’s also less reliable. “We [humans] are variable,” chuckles Babensee. “We do things differently every day.”

Via wireless, sub components continually report their status and health. Vibration, heat, pressure, temperature, stress. Anything off the norm is picked up and flagged, diagnosed -and corrected -before it can cascade into a plant-wide shutdown.

Wireless sensors and technology save shoe leather and sidesteps many problems. Reliable and real-time immediate, they’re cost effective too. Hard-wiring a particular component could cost $100,000 on average; Babensee says wireless can cut the hit by three quarters.

Wireless also goes where no hard-wire sensor has easily gone before. For example, rotating machines such as fans, turbines and lime kilns. Before, getting accurate and continual temperature profiles in hot, harsh, dirty environments like lime kilns meant lots of wire, contact brushings and crossed fingers. With wireless, it’s not.

Wireless also highlights what Jim Cahill, industry blogger and marketing communications manger for globe-spanning

U. S.-based Emerson Process Management, calls the new “intelligence” seeping down into mills. On the floor, Cahill says the potential for wireless is open ended. “Just wait for the fertile minds of the engineers to pick it up and run.”

Like a living organism that’s healthy on the cellular level, the cumulative effect is a far more efficient overall operation. Rather the usual big, expensive hos

t-level application squatting atop the main system and treating the system as a collection of proportional-integral-derivative (PID) control loops, top-to-bottom computerization increases overall functionality.

One example is EDSA Micro Corporation and its Paladin Live software that, according to EDSA, utilizes “neo-cortical pattern/sequence recognition technology” to learn as it goes along. Data points are aggregated or collected to accurately predict the location, context and even the cause of impending electrical failures long before they become reality.

For now Babensee says there’s “a bit of reluctance” among mill management to use wireless for critical-process control. However, for diagnostics purposes the acceptance is growing. “It’s really just starting. It’s the tip of the iceberg.”

Ed Schodowski calls wireless technology a “leap-frog area” that could carry the industry far . . . but perhaps not just yet. Yes, the engineers and other front-line types are embracing wireless and new optimization technologies but the enthusiasm needs to float farther upstairs: “I don’t think the focus for management is quite there yet. I see it happening but it takes time.”

Don’t Forget the Warmware . . .

New gadgets are great, fancy software is impressive but without trained human minds and hands to interpret and do the follow through, the best technology is nothing.

Chris Bassett, division manager for Universal Dynamics and based in Nanaimo, BC, says any optimization plan should emphasis proactive maintenance. “It’s key.”

Rather than getting locked to maintenance schedules and/or fixing something after it breaks, Bassett believes good maintenance teams venture beyond the status quo: “They should be looking for ‘opportunities’ that will create internal optimization. They should be looking forward.”

In the industry, this means proactive reliability-centered maintenance (RCM) for critical assets, especially hard working, hard-wearing rotating equipment such as pumps, fans, refiner motors and steam turbines. Log a ‘history’ of each components and asset to anticipate possible failures before they happen.

Bassett remembers his stint as plant engineer at Peace River Pulp in the early to late 1990s. The maintenance manager didn’t want “his people sitting there fixing broken things” but instead “created an environment where the [maintenance] guys took ownership” and actively sought to improve overall operations.

If a guy spent the shift in the office reading manuals and musing deeply, that was quite okay with the maintenance chief. Ditto with the folks upstairs. Recalls Bassett: “They were very engaged; it was a good rapport between operations and maintenance, there for a common goal. It worked very well.”

. . . But Don’t Overload It Either

Canadian pulp and paper mills traditionally relied on large internal work-forces doing myriads of different tasks. Today, more mills look to technology and hired guns -outside expertise and contractors -to perform various technical services and reduce costs and manpower. For example, computerized ‘floor systems’ can analyze samples in real time, right there, and plug the data into the control system immediately.

The upside: improved efficiency and a continual cross-fertilization of knowledge and applications of ‘outside’ technology to improve the pulp and paper industry’s overall viability. The downside: the workforce that is adversely affected by the current technology, never mind what’s coming down the pipe.

Labour costs and inefficient use of personnel are a big reason why Canadian mills struggle to remain competitive. As Emerson’s Ed Schodowski notes, a true optimization plan matches the right technologies to the right people and with the right training.

“The skill set needs to move upward to apply these types of products and get the benefits out of them,” says Schodowski. “The operator becomes more of a ‘process manager’ than somebody who just stops and starts motors.”

Agreed, says Chris Basset, division manager for Universal Dynamics in Nanaimo, BC. The reality and potential of optimization technologies such as wireless goes beyond mere data sensing. Properly applied, it frees up humans to work better, more efficiently and more happily.

One example: wireless and chip handling. Rather than wait for control to remotely activate a conveyor or swinger, Bassett says it makes more sense if the caterpillar or front-end loader operator can take command, wirelessly control the conveyor, talk to the trucks and so forth.

Given the power to do things, rather than endure the mundane boredom of ‘plowing chips’ or whatever, also creates a happier, more involved workforce. Says Bassett: “There’s actually a reward for the guys. They’re doing more and it’s more interesting.”

As the domestic workforce ages and competition from overseas increases, so does the realization in the industry to the benefits of optimization and process control and the need to invest in, and use, these tools.

By reducing or eliminating certain functions and maximizing other areas, individual mills and the industry itself have an opportunity to invoke ‘technical changes’ to retain and retrain the right people, cut costs and move the industry into more productive areas and activities . . . and ultimately give those lumbering overseas giants reason to sheer clear.

Goldilocks and the Three Bears? Or perhaps Jack in the Beanstalk. The giant did not fare well in that encounter.

Print this page